Winds That Shape the Sea

Global Wind Systems Guiding Every Voyage

7 min read

Each ocean has its own rhythm, subtle shifts, powerful flows, and seasonal pulses shaped by Earth’s global wind systems. For sailors, understanding these patterns is more than just science, it’s the key to a safer, smoother, and more rewarding journey. In this post, we’ll explore the major wind systems and weather zones that shape life under sail: the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), the Trade Winds, the Westerlies, Monsoons, Variable Wind Zone, Tropical Squalls, and Tropical Revolving Storms. Brace yourself, it's time to ride the winds of the world.

☀️ Solar Heating and the Birth of the ITCZ

The equator receives more direct sunlight than the poles, heating both the air and the ocean. As a result, warm air rises near the equator, creating a low-pressure zone known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone or ITCZ. In this region, air from both hemispheres rushes in to fill the low pressure, but because the winds come from opposite directions, they cancel each other out horizontally. The motion becomes mostly vertical. Hot, moist air rises, often forming towering clouds, squalls, and thunderstorms.

This zone is also called the “Doldrums”, a sailor’s nightmare in the days before engines, because wind can become light, variable, or completely absent for days. At the same time, the combination of intense sun and rising humid air makes the ITCZ hot, sticky, and stormy.

The ITCZ doesn’t stay fixed at the equator. Because Earth is tilted on its axis, the location of maximum solar heating shifts north and south with the seasons:

During the equinoxes (March and September), it sits near the equator.

In Northern Hemisphere summer, it shifts north.

In Southern Hemisphere summer, it shifts south.

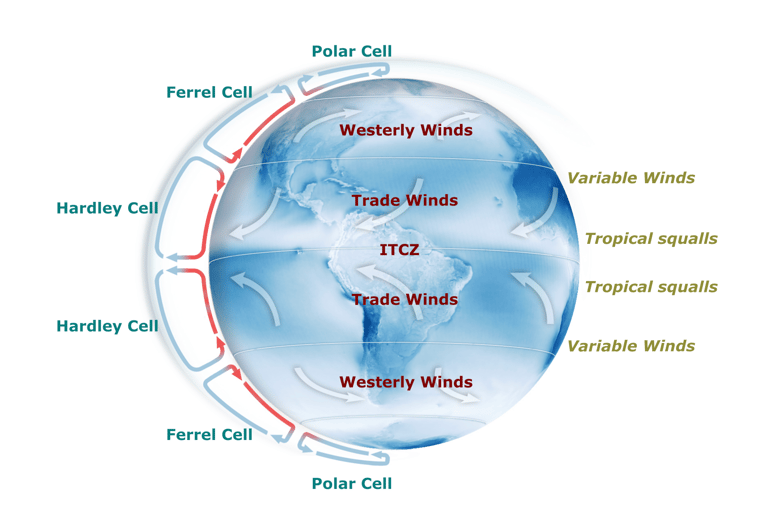

🌬️ How Trade Winds Form: The Hadley Cell

Now, how do the trade winds fit into this? The term "Trade Winds" actually comes from the old English word "trade", meaning a regular path or track. These winds became essential during the Age of Exploration, when European sailing ships relied on them to travel faster and more safely across the Atlantic, particularly on routes like Europe to the Caribbean. But what exactly are trade winds and how do they form?

The rising air at the equator doesn’t just vanish. It moves high in the atmosphere toward 30° latitude, where it cools and sinks, forming part of a circulation pattern called the Hadley Cell. This sinking air at around 30°N and 30°S creates high-pressure zones. Surface air then flows back towards the equator to replace the rising air, creating a steady equatorward wind. Because Earth rotates, this flow is deflected by the Coriolis effect:

In the Northern Hemisphere, the air is deflected to the right, forming the northeast trade winds.

In the Southern Hemisphere, it deflects to the left, forming the southeast trade winds.

These winds are generally steady and reliable, typically blowing at 15–25 knots, with good weather, blue skies, and only occasional small clouds. The pressure remains relatively stable.

Trade winds are not the same all year. They are strongest and most reliable during the dry season of each hemisphere. Why? Because:

The temperature contrast between the subtropics and the equator is stronger and more stable in the dry season.

The ITCZ moves away from the region, reducing the influence of squalls and calm zones.

In the Northern Hemisphere's dry season (Nov–May), the ITCZ moves south, strengthening the NE trades.

In the Southern Hemisphere's dry season (May–Oct), it moves north, boosting the SE trades.

The dry season also brings fewer storms, less convection, and less atmospheric interference, which means more consistent winds.

🌎 Fun Fact: The 12-Hour Pressure Pulse

When sailing in the Trade Winds, even in fair weather, you might notice that air pressure rises and falls about every 12 hours. This is due to solar atmospheric tides. Those are not related to ocean tides, but to heating of Earth’s atmosphere by the Sun. As the Sun heats the atmosphere unevenly during the day, it causes the air to expand and contract in a rhythmic way, creating global-scale pressure waves. These lead to a twice-daily pressure cycle that can be observed even when no weather systems are nearby.

CREDIT: Background from NASA

🧭 Westerly Winds

At the edge of the trade wind zone, the westerlies begin. This are prevailing winds that blow from west to east. These winds dominate the region between roughly 30° and 60° latitude in both hemispheres. Unlike the Hadley Cell, which drives air toward the equator, this region is governed by the Ferrel Cell, where surface winds blow toward the poles. The westerlies are typically stronger and more variable than the trade winds, especially in the Southern Hemisphere, where there’s less land to disrupt their flow. In these latitudes, storm systems frequently pass through, bringing rapid wind shifts and powerful gusts. Between 30° and 40°, you can expect 10–20 knots, often gusty and inconsistent. Further south, in the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties (40°–60°), wind speeds can reach 20–35+ knots, often sustained, with large ocean swells. This makes the westerly zone fast and powerful for eastbound sailing, but also challenging and sometimes dangerous, especially when heading west or navigating around major capes like Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope.

🌀 Variable Winds

Right between the steady trade winds and the stronger westerlies, typically around 25° to 35° latitude lies the variable wind zone, also known as the subtropical high or horse latitudes. It sits at the boundary between the Hadley Cell and the Ferrel Cell, where air sinks, creating a zone of high pressure with light, shifting, or completely calm winds. For sailors, this can mean slow progress, intense sun, and the need to motor for long stretches. While usually narrow, it’s a zone that requires careful timing to cross efficiently and reach the more reliable wind belts beyond.

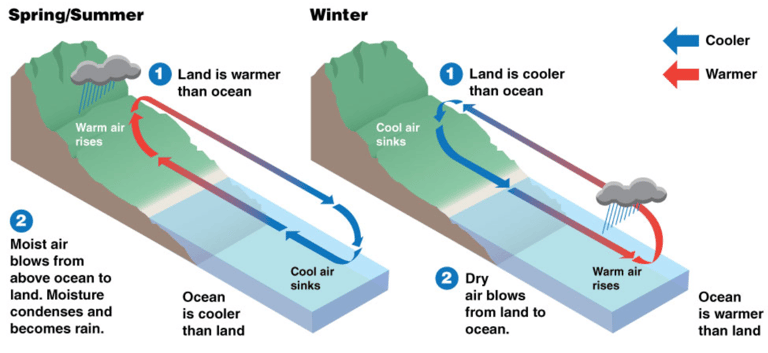

💨 Monsoons

Monsoons are large-scale seasonal wind systems caused by the unequal heating of land and ocean, and they reverse direction between summer and winter. They occur mainly in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia and sit between the Hadley Cell and the Equatorial region, where intense heating drives strong seasonal circulation. The name "Monsoon" is derived from the Arabic word with the meaning "Seasons". This is because in summer, land heats faster than the sea, drawing in moist ocean air and creating powerful southwest monsoon winds with heavy rain. In winter, the pattern reverses, bringing dry northeast winds from the continent. For sailors, monsoons mean timing is everything. Riding the right seasonal wind can make for fast, efficient passages, while going against it can be dangerous or impossible.

CREDIT: NOAA/JPL

⛈️ Storms

Tropical squalls are sudden, short-lived but intense storms that form mainly near the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), where warm, moist air from both hemispheres converges and rises. They are most common in tropical regions, typically 5° to 15° latitude north or south of the equator, and occur year-round, but are more frequent and intense during the wet or rainy season, when sea surface temperatures are high and humidity is extreme. Squalls usually form in the late afternoon or night, triggered by strong convection over warm ocean water. They can bring wind gusts of 25 to 40 knots or more, heavy rain, lightning, and rapid wind shifts. Though they usually last less than an hour, their impact on sailing can be significant, especially if you're caught unprepared with too much sail up or poor visibility.

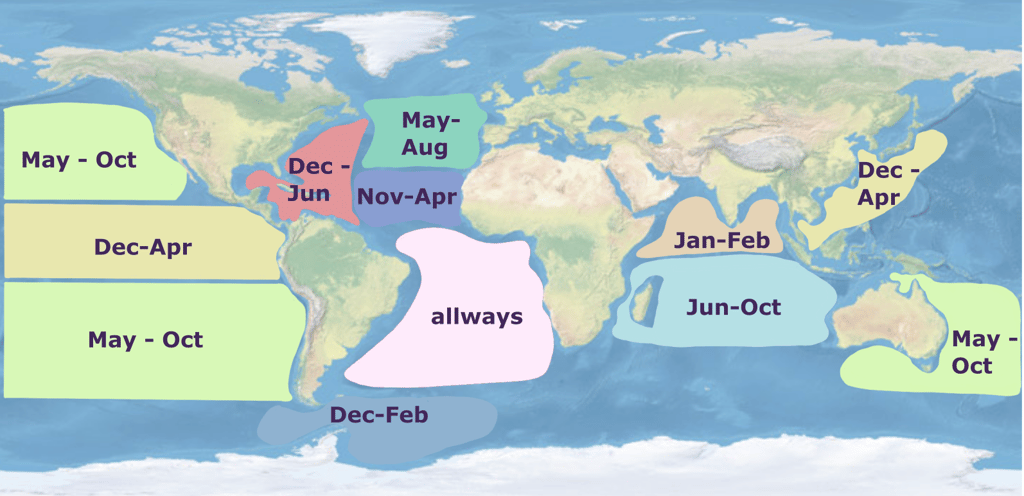

Tropical revolving storms are large, powerful low-pressure systems that form over warm tropical oceans, usually between 5° and 20° latitude north or south of the equator. They go by different names depending on region: hurricanes in the Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, typhoons in the Northwest Pacific, and cyclones in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific. These storms develop when sea surface temperatures rise above 26–27°C (79–81°F), fueling intense evaporation and convection. As warm, moist air rises and spins due to the Coriolis effect, it forms a rotating system with a calm eye at the center and violent winds surrounding it. Tropical storms can grow into massive systems with sustained winds over 64 knots (74 mph or 119 km/h), bringing destructive gusts, towering waves, extreme rainfall, and dangerous storm surges. If you want to learn more read our blog article about Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones.

They follow seasonal patterns:

In the North Atlantic and Caribbean, hurricane season runs from June to November, peaking in September.

In the Northwest Pacific (Asia), typhoons can form nearly year-round, but are most frequent from May to October.

In the Southern Hemisphere (Indian Ocean and South Pacific), cyclone season runs from November to April, peaking around January to March.

For sailors, tropical revolving storms are among the most dangerous conditions at sea. Routes must be planned carefully to avoid cyclone zones in their active seasons, and anyone sailing in the tropics should monitor forecasts closely, have storm avoidance plans, and understand safe latitudes and timing for ocean crossings.

Credit: Background NASA

📚 Our Book Recommendations for Route Planning

We highly recommend The Voyager’s Handbook by Beth A. Leonard. It’s a thorough guide to bluewater cruising, with clear explanations of global weather patterns, onboard forecasting, and heavy weather tactics. 👉 Buy on Amazon (Ad)

The beautifully illustrated books by Jimmy Cornell that helped us better understand global sailing routes and their weather systems:

🌍 World Voyage Planner by Jimmy & Ivan Cornell – A great overview of local and global weather patterns, sailing seasons, and route planning fundamentals. 👉 Buy on Amazon (Ad)

🗺️ World Cruising Routes by Jimmy Cornell – A detailed 600+ page guide to over 1,000 sailing routes worldwide, with seasonal wind patterns, current information, and ideal timing for each passage. 👉 Buy on Amazon (Ad)

If you’d like to read more, follow our journey, and support what we do, don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter or follow us on social media. Every bit of encouragement helps keep the adventure going and we’d love to have you aboard!